Hack to the Future - Frontend

Table of Contents

- Hack to the Future - Frontend

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Setting the Time Circuits to the late 90s

- 3. The Early Web - Layout and Design Practices

- 4. The Plugin Era – Flash and Friends

- 5. The JavaScript Library Explosion

- 6. CSS Workarounds and Browser Quirks

- 7. Markup of the Past

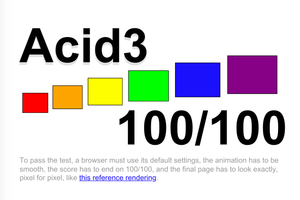

- 8. Tools and Workflow Relics

- 9. Legacy Web Strategies

- 10. Tests and Standards of Yesteryear

- 11. What Still Matters - Progressive Enhancement

- 12. Lessons for the Future

- 13. Post Summary

1. Introduction

Context

So over the last few months at work, I've been conducting interviews to hire Frontend Developers for a number of new projects we have in the pipeline. It was only when looking at CV's that it struck me, a lot of these candidates weren't even born when I first started in my Web Development career! So I thought maybe developers getting into a Frontend Developer career today, may want to learn a bit about what it was like when I first started (that sentence just makes me feel old! 👴)

Looking back at “legacy” practices

Why would we want to look back on legacy best practices on the web? Other than the obvious academic and for general interest reasons?

Studying past best practices and legacy systems is crucial for understanding the evolution of technology and making informed decisions today. By examining the problems old practices were designed to solve, we gain a deeper appreciation for current best practices and avoid repeating past mistakes. As the philosopher George Santayana once said:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

This historical perspective also reveals enduring principles like progressive enhancement, which remains vital for creating accessible and resilient systems on the web.

Lessons we can apply today

For developers, understanding past methodologies is essential for properly maintaining and modernising existing systems in the future without causing critical failures. This historical knowledge will ultimately help them navigate the complexities of older codebases, to ensure they make informed decisions about how to update or replace components. Above all, reflecting on the past can help us come up with creative new ideas and prevent us from blindly following new trends. This perspective also provides a comprehensive view of how the web has evolved, grounding our current practices in a deeper understanding of the technology's history.

This process of building on past knowledge is a fundamental aspect of human progress. Just as civilizations learn from historical events to avoid repeating mistakes, developers can learn from the successes and failures of past technological eras. It's how humanity has always evolved. By building upon the accumulated wisdom and experience of those who came before us. By studying the mistakes and triumphs of the past, we improve our own work and contribute to the continuous cycle of innovation and learning that drives our entire industry forward.

2. Setting the Time Circuits to the late 90s

My first website build

In 1998, while working toward my GCSEs, I became interested in art and design, this was partly thanks to having an art teacher as my form tutor throughout secondary school. That influence, combined with the opportunity to take a double art GCSE for the same effort as a single GCSE, made the choice a pretty easy one! GCSE Art, here I come!

At the same time, I was already immersed in the emerging world of the internet, spending many hours online discovering a passion for many areas of computing and online gaming thanks to QuakeWorld Team Fortress, despite the frustration it caused at home by tying up the phone line all hours of the day, oh how I loved my US Robotics 56K modem, with its 120-150 ping! Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) or any form of broadband was still many years away for most people!

I was never exactly blessed with traditional artistic talent, painting, drawing, all of those art forms just wasn’t my thing. But I spotted an opportunity to combine my love of technology with the art curriculum. Back then, there were only about 2.4 million websites in existence worldwide. Most businesses and schools (including mine), were firmly offline. So, I proposed building a website for my final art project. To my surprise, my art teacher was absolutely thrilled with the idea. It turned out to be a first for the school and, as I later discovered, a first for the entire exam board too. Shock horror: I was ahead of the curve once. The curve has been safely ahead of me ever since.

I ended up creating a website for a fake record label, complete with a dreadful album cover, fictional artist, and made-up discography. Honestly, I wish I still had it! It was gloriously awful! I don’t recall much, but I remember the site used a <frameset> with three <frame> elements. The top frame displayed the logo, the left frame held the navigation menu, and the main frame was used for the page content.

The logo, by the way, was crafted in a program called 3D Text Studio (or something similar to that) that churned out spectacularly cheesy animated text like this! From a web performance perspective, that single GIF exceeded 2 MB. On a 56K modem, which was the standard connection for most users of the web at the time, that translates to a 6-minute loading time for just that GIF! Fortunately, it was never hosted online and was presented to the examiners directly from my local machine.

Long story short… the examiners loved my little website and I got a double A* Art GCSE for my effort!

So what's all this preamble leading too? Well, this is just a long-winded way to tell you (again) that I'm old… 😭

The late 90s web landscape

There have been some things I've noticed while questioning candidates in interviews recently, many candidates don't have the faintest idea of some old methodologies used in the world of Frontend, especially during the "unstable" periods of the web like the late 90s and early 00s:

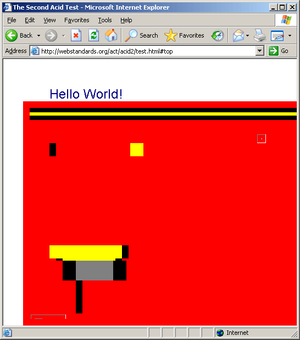

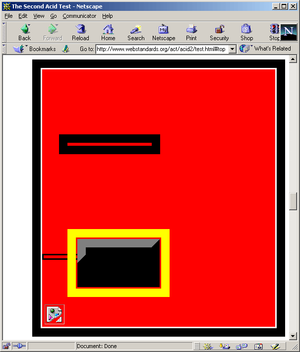

- first browser war (1995–2001): Internet Explorer vs Netscape Navigator.

- second browser war (2004–2017): Internet Explorer vs Firefox vs Google Chrome.

Being a Frontend Developer in the late 90s was both fun in terms of innovation, but also exceedingly stressful due to the instability of the web platform! A prime example being cross-browser development. What worked in Netscape, often looked very broken in Internet Explorer (and vice versa)! And if you had clients who were looking for "pixel perfect" designs across all browsers, you were in for a bad time!

Throughout this period, a plethora of methodologies, tools, and workarounds were developed to address deficiencies in the web platform. And that’s what the rest of this post will delve into. Buckle up folks, we are about to time travel to an era when the internet started with the screeching of dial-up noises and I still had brown hair!

3. The Early Web – Layout and Design Practices

Photoshop PSDs as the “single source of truth”

Using Adobe Photoshop Documents (PSD) as a single source of design truth was a very common practice in the early days of web design. This was particularly common when design and development teams were siloed. A designer would create a PSD file that was intended to be precisely what the website would look like in the browser.

Issues

There were no considerations made for page structure, behaviour, and interactions. These fixed layout PSD's encouraged bad practices like:

- Fixed page dimensions e.g. 1024px x 768px as a static canvas.

- 1:1 mapping of Photoshop file to web page, which was rarely achievable, especially given cross-browser inconsistencies with page rendering.

- Lack of fluid or responsive design. I realise responsive design wasn't "a thing" at this time, but could it have been adopted sooner if fixed-width PSD workflows hadn't ever taken hold?

- The technique was more suited to static layouts, like print design, rather than web design.

- There were issues tracking interaction states like anchors with hover, active, disabled, and focus.

- Dynamic content was difficult to visualise (e.g., the rendering of different lengths of text in the browser).

- Poor accessibility adaptations, (e.g., increased font sizes, high-contrast modes weren’t considered in the design files).

The only way to solve many of these issues would be to create multiple PSD's to hold all these different design assumptions. And in doing so, file management and design revisions would quickly become impractical and prone to being incomplete or inconsistent.

Broken team collaboration

The use of PSD's as the single source of truth broke how teams could collaborate and innovate. This was because:

- Developers would often have to interpret or translate the PSD design manually without the help of designers (e.g. due to siloed teams and strict job roles).

- Changes in the design required round-trips to designers, rather than being evolved collaboratively in code.

- Small team bottlenecks were common e.g. all design or development decisions needed to go through individuals rather than a whole team.

- Files became outdated rapidly leading to teams working on outdated designs without realising it.

- Designers often came up with designs that simply couldn't be built with the web technologies that existed at the time, especially when their designs were expected to work across different browsers.

Modern Alternatives

I'd like to think that designers using Photoshop for modern web design is a thing of the past, given the vast number of tools and techniques that are way more suited to the job than Photoshop ever was. Modern teams typically use:

- Design tokens and internal component libraries as the "single source of truth".

- Figma or similar tools with structured, token-aware components.

- Living style guides and code-driven prototypes (e.g., Storybook).

- Clear handoffs between teams using tools like zeroheight, or integrated design-to-dev platforms.

The advantage of using these modern collaboration tools enables design and development teams to share the same language and source of truth, rooted in reusable, well-tested, and accessible components.

Photoshop PSDs Summary

In the early days of my frontend career, slicing PSDs was second nature, but that workflow is now obsolete. Using Photoshop as a "single source of truth" leads to siloed teams, rigid layouts, and poor collaboration. It ignores responsiveness, accessibility, and the realities of modern web development. Today, tools like Figma, design systems, and component libraries enable faster, more inclusive, and collaborative workflows. If you’re still building from PSDs, it’s time to move on! As the web has evolved, it is imperative that we all do the same.

Frame-Based Layouts

The Frame-based layouts were introduced into browsers to solve a specific set of problems. These were:

- To allow static content like navigation menus to remain in place while only the main content of the page gets updated on navigation.

- To Reduce the amount of data transferred over the network, since only one part of the page would need to be loaded. This was important at the time as remember in the late 1990s and early 2000s, broadband for most people simply wasn't available. If you were very lucky (and had the money), you'd be able to get an Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) line installed in your home, but it was mostly online businesses that had the money (and justification) for this type of connection, even ISDN wasn’t particularly quick. Adjusted for inflation you'd be looking at £60 to £80 per month for a 0.128 Mbps connection!

- To simulate a more app-like experience before JavaScript (JS) and CSS became more standardised and mature.

Example

For those curious here's an simple example of an HTML page using frames:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Frameset//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/frameset.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<title>Simple Frame Example</title>

</head>

<!-- Note no Body element: 2 vertical columns -->

<!-- 30% width the menu.html document -->

<!-- 70% width for the main content of the page -->

<frameset cols="30%,70%">

<frame src="menu.html" name="menuFrame">

<frame src="content.html" name="contentFrame">

</frameset>

</html>Notes:

- To use

<frame>and<frameset>you needed to use a specific HTML 4.01 Frameset DOCTYPE, in the index.html file. - In my example, for a single HTML page you'd have to maintain 3 HTML files (index.html, menu.html, and content.html).

- Each frame was like a mini browser window that loaded its own HTML document.

Problems

Unfortunately, there were a number of major issues with Frame-Based Layouts:

- Terrible user experience: the use and navigation of frames was confusing for users, since you effectively had multiple browser panes in a single page. The URL bar would often remain static even as the content of the page changed.

- Poor Accessibility: Screen readers and other assistive technology struggled to navigate frames, making it incredibly difficult for users with disabilities to understand the page content and overall page structure.

- Limited Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) compatibility: Even Search engines of the day struggled to understand the index pages built within frames. This lead to poor visibility in search results, as crawlers frequently failed to understand the relationship between the different frames.

- Navigation and Browser Compatibility: Because the back and forward buttons did not consistently produce the desired results, frames disrupted the navigation history, making it difficult for users to find their way around. The fact that different browser vendors weren't aligned with how frames should work in browsers lead to cross-browser issues too.

- Bad for security: Frames allowed for security risks like clickjacking. This is where an attacker gets a user to interact with a page that contains malicious content without the user even realising. Modern browsers now include protections to stop these types of security issues.

Modern Alternatives

- Modern CSS Layouts: Flexbox and Grid allow for responsive layouts without compromising navigation, accessibility, and SEO.

- Single Page Applications (SPAs): Frameworks like React, Angular, and Vue allow developers to load page content dynamically without the need for full-page reloads. Be careful though, these libraries come with their own inherent issues if not used correctly!

- Server-Side Rendering and Partial Updates: techniques like server-side includes, AJAX, or component-based rendering to update portions of a page efficiently.

Frame-Based Summary

As mentioned in the introduction at the start of this post, my first website was built using frames! I sincerely hope you never have to maintain a frame-based website! But given the enormity of the internet, it is almost certain websites exist somewhere out there, having been untouched for decades! If you do come across one remember to take a quick peek at the source code, it's like looking back in time! They once served a purpose in the early days of the web but are now considered obsolete. Their usage introduced more problems than they solved, and have been replaced with techniques that are more performant, accessible, and maintainable. Any modern website should be using semantic HTML, CSS-based layouts, and progressive enhancement.

Table-Based Layouts

In the late 1990s and early 2000s table-based layouts were a common technique for building a web page structure: A simple example of what this would look like is below:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<title>Table Layout Example</title>

<!- Very simple CSS to modify the key elements in the table-based layout -->

<style>

body {

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

}

td {

padding: 10px;

border: 1px solid #ccc;

}

.header {

background-color: #f2f2f2;

text-align: center;

font-weight: bold;

}

.nav {

background-color: #e0e0e0;

width: 200px;

vertical-align: top;

}

.content {

background-color: #ffffff;

vertical-align: top;

}

.footer {

background-color: #f2f2f2;

text-align: center;

font-size: 0.9em;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<table width="100%" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="0">

<!-- Header -->

<tr>

<td colspan="2" class="header">

My Table-Based Web Page

</td>

</tr>

<!-- Body -->

<tr>

<!-- Navigation -->

<td class="nav">

<ul>

<li><a href="#">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="#">About</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

</td>

<!-- Main Content -->

<td class="content">

<h2>Welcome</h2>

<p>This layout uses an HTML table for structure, which was common before CSS-based layouts became standard.</p>

</td>

</tr>

<!-- Footer -->

<tr>

<td colspan="2" class="footer">

© 2025 Example Company

</td>

</tr>

</table>

</body>

</html>Why was it used?

At the time CSS and layout techniques were inconsistent and unstable across browsers. Developers looking for stability in cross-browser rendering turned to tables in order to do this. At the time, tables offered:

- Predictable cross-browser rendering

- Control over alignment, spacing, and sizing

- Ability to nest elements in a grid-like structure

It was very common to see nested tables and transparent "spacer GIFs" in invisible table cells to control these layouts more precisely. You'd often find logo's, sidebars, navigations, footer, and content areas all laid out within a deeply nested HTML table in order to achieve the layout and design that was required.

Why was it so bad?

The first and hopefully most obvious point is that the <table></table> element was intended for the display of tabular data. The fact that it was used as a workaround for the lack of standardised layout techniques, shows the ingenuity of developers at the time.

Unfortunately, the use of tables for layout came with many considerable downsides, these included:

- Semantics: As mentioned, tables should represent structured data, not layout. Misusing them confuses assistive technologies and harms accessibility.

- Maintainability: Table-based layouts are challenging to read, modify, or scale. Small changes often require restructuring entire layouts.

- Responsiveness: They are rigid and not suited to fluid or responsive design, that was to come a number of years later.

- Performance: They delay rendering because browsers need to calculate the entire table layout before painting it to the page.

Is the technique still used?

There are some areas where table-based layouts may still be seen:

- Legacy code bases that desperately need to be refactored, I can imagine there are many internal systems across the world where table-based layouts are still used. I’d imagine the conversation about modernising goes something like this… "If it still works, why change it?". Very short-sighted I know!

- Table-based layouts are still widely used in emails due to the very limited support for CSS in email clients. It's not always the lack of support, it's the fact that many clients simply strip out any CSS in the process of rendering the email HTML.

- To give you an example of how bad it still is, from Outlook 2007+, Microsoft switched to Microsoft Word as the HTML rendering engine! And it's still in use today with Outlook 365! I did my fair share of HTML emails as a Junior Frontend Developer, the internationalised versions were the worst! Using the same table-based layouts for 19+ languages is never going to work well, especially with languages like German with their huge word length! Sorry… rant over!

- They are often still used in PDF generation tools e.g. data-driven print views: invoices etc.

Modern alternatives

Modern CSS offers clean, semantic, and powerful layout tools, including:

- Flexbox: One-dimensional layouts (ideal for nav bars, toolbars, etc.)

- CSS Grid: Two-dimensional layouts (ideal for full-page layout and complex structures)

- Media Queries: Enable responsiveness across devices

- Container Queries (still an emerging technology): Context-aware layout changes.

Table-Based Summary

Table-based layouts are a throwback to a bygone era, thankfully! The years of building HTML emails has scared me for life! As they were developed during a period in which CSS was inadequate for the task. Developers had to get creative to wrestle with browser quirks, and tables were the go-to workaround. Thankfully, these days, we’ve moved on to semantic HTML and proper CSS that actually does what we need (for webpages anyway). It’s cleaner, more flexible, and maintainable, and way better for accessibility.

Quirks Mode Layouts

This topic is covered in more detail later in the blog post, but I’ll briefly mention it here for completeness.

It's important to realise that Quirks Mode Layouts weren't only limited to Internet Explorer (IE). It originated with Internet Explorer, but it was not exclusive to IE. Not only that, it later became a cross-browser convention in order to preserve the compatibility with many web pages on the internet. As that's the primary rule to consider when rolling out any new technology changes on the web. Whatever you do, "don't break the web!".

For example, if a vendor released a new browser feature that wasn't backwards compatible with earlier versions of web pages, then you have a major issue as you've just broken the web! I talk about XHTML 2.0 later in the post, as it is a prime example of a proposed technology that would have broken the web. This backwards compatibility was the sole purpose of Quirks mode. It gave modern browsers the ability to switch between:

- Quirks Mode: Mimic pre-standards behaviour. Used for old, non-compliant pages.

- Standards Mode: Adheres to modern web specifications (W3C and WHATWG standards).

- Almost Standards Mode: The same as Standards mode only with one exception, table cell line-height rendering. This was to preserve layouts that used inline images inside HTML tables.

How were layouts triggered?

The browser decided which layout mode to use from the list above purely from the DOCTYPE used on the page. For example:

Trigger Quirks mode

This DOCTYPE will trigger Quirks mode layout:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN">It looks valid, but it is missing the system identifier (URL) therefore it is a malformed DOCTYPE so Quirks Mode is triggered. A valid DOCTYPE is given below for comparison:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">That missing URL in the DOCTYPE is vital. Quirks Mode would also be activated if a page did not have a DOCTYPE or was not identical to the valid DOCTYPE given above in any way. IE even had a really nasty habit of triggering Quirks Mode if any character was output in the page source before the DOCTYPE. This included invisible characters and new lines and line returns too! As you can imagine, it made debugging issues an absolute nightmare!

Almost Standards Mode

The following DOCTYPE's will trigger Almost Standards Mode:

- HTML 4.01 Transitional (with full system identifier):

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">- HTML 4.01 Frameset (with full system identifier):

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Frameset//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/frameset.dtd">- XHTML 1.0 Transitional:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">- XHTML 1.0 Frameset

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Frameset//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-frameset.dtd">Standards Mode

And lastly and most importantly for modern web development. This is the DOCTYPE you should be using to trigger standards mode in all modern browsers:

<!DOCTYPE html>This simplified DOCTYPE was brought in as part of the HTML5 Specification after 6 years of standardisation (2008–2014).

Why was this version created?

As outlined in all the examples above, previous DOCTYPE versions were:

- Long

- Error-prone

- Required both a public and a system identifier

- Affected rendering modes (Quirks, Almost Standards, Standards)

In order to solve these issues this the new DOCTYPE:

- does not reference a Document Type Definition (DTD) as (HTML5 no longer relies on SGML-based validation).

- only has a single purpose: to trigger Standards Mode in all modern browsers.

Quirks Mode Summary

As we have discussed above, Quirks Mode wasn't an IE exclusive layout mode. It was introduced into all browsers in order to "not break the web". To ensure your website uses Standards Mode, use:

<!DOCTYPE html>And remember it must be the first characters in the source code on the page!

Iframe Embeds for Layouts or Content

If you've already read the Frame-based Layouts section above, then this section will be very similar. Although both are now considered legacy techniques, they come with distinct differences.

Frameset

As I discussed earlier here's example <frameset> code:

<!-- column 1 25% width / column 2 75% width -->

<frameset cols="25%,75%">

<frame src="nav.html">

<frame src="main.html">

</frameset>- The

<frameset>tag completely replaced the<body>tag and allowed developers to split the browser window into multiple, scrollable, resizable sections. - Each section (

<frame>) loaded a separate HTML document (as seen in the code above). - This technique was intended to use them as a layout structure. e.g. different parts of the User interface (UI) came from different HTML documents.

- Navigation in one frame would control the content in another frame.

Inline frames (Iframes)

These were introduced later in the HTML 4.01 Transitional specification. Example <iframe> code is found below:

<body>

<iframe src="content.html"></iframe>

</body>You will immediately notice the difference, using an <iframe> doesn't replace the <body> tag, it embeds an external HTML page into the original page.

- The usage of iframes was to embed content into other pages, not structure the whole layout.

- iframes were used to load external or isolated content within a single, self-contained HTML page.

User Experience

Both methods came with issues, but iframes were slightly better but still caused significant problems:

- Embeds could be styled and resized, but remained isolated from the parent.

- Navigation, SEO, and accessibility were still severely impacted when misused.

Standards and Browser Support

Framesets were deprecated and completely removed from the HTML5 specification, modern browsers either no longer support them or support is very limited without the correct DOCTYPE.

Iframes are still a part of the HTML5 specification, but they come with limited use cases, including:

- Secure sandboxing

- Third-party embeds

In fact, the performance of iframe embeds has recently been improved by browsers vendors adding support for loading="lazy" on iframes thus allowing the browser to delay loading until the iframe is in the viewport.

Security

Thankfully, iframes are more secure on the modern web thanks to attributes like:

Although the use of iframes still needs careful consideration for content integrity, cross-domain policies, and maintainability. They can still introduce security vulnerabilities such as:

- Clickjacking

- Cross-site scripting (XSS) exploits.

- Cross-origin resource sharing (CORS) exploits.

Can I still use them?

Yes, iframes are still a part of the HTML5 specification, so you can still use them, but you should try to only use them in specific scenarios where required. For example, when you need to embed third-party content into a website. This is often seen in banking on the modern web, when you are paying for something online. The final step of the transaction frequently loads an iframe from your bank asking to verify your purchase, usually via some form of Multi-factor Authentication (MFA) e.g. SMS, banking app approval on your phone. While iframe embeds aren't specifically required for PCI compliance. Many online merchants tend to implement them along with 3D Secure authentication to help reduce PCI scope and exposure.

Modern alternatives

As mentioned in the Frame-Based Layouts section, there are a number of modern alternatives rather than using iframes for page layout, modularisation, and code isolation. These include:

- Modern CSS Layouts: Flexbox and Grid allow for responsive layouts without compromising navigation, accessibility, and SEO.

- Single Page Applications (SPAs): Frameworks like React, Angular, and Vue allow developers to load page content dynamically without the need for full-page reloads. Be careful though, these libraries come with their own inherent issues if not used correctly!

- Server-Side Rendering and Partial Updates: techniques like server-side includes, AJAX, or component-based rendering to update portions of a page efficiently.

Iframe Embeds Summary

Using iframes for modularisation and isolation is now seen as a legacy approach and should generally be avoided on the modern web. That said, they still have a place for things like third-party embeds. I remember the early days of Facebook marketing, iframes were everywhere and an absolute nightmare to work with, especially when trying to get the sizing right within their UI. Urghh!

Pixel-Perfect Design

Pixel-perfect design is a now outdated design approach that was once considered the gold-standard in frontend development. The presented UI on the web page was intended to be a pixel-perfect replica of the design mockups.… If that sounds like a ridiculous and totally unworkable strategy, then I can confirm, yes it was!

What the technique means in practice

- Strict visual fidelity: Developers were expected to reproduce every element of a design using the exact measurements, colours and fonts given in a static design file like a Photoshop Document file (PSD).

- Close alignment with design tools: The priority while using this technique was to match the layout in the design document, no matter what. Inconsistencies across various browsers, not to mention differing screen sizes and user preferences, frequently made this an impossible task.

- Used in fixed-resolution environments: The technique worked reasonably well in the era of desktop-only websites with very few fixed screen sizes (e.g. 800×600, 1024×768).

Why is it considered legacy?

- Responsive design is now standard

- Modern devices now range from the size of watches, all the way up to ultra-wide monitors and TV's and everything in between. Pixel perfect design fails on both smaller and larger size screens.

- Accessibility and user preferences

- Modern Accessibility-first design requires designs to be flexible in terms of layout and scaling. For example, WCAG 2.2 Success Criterion 1.4.4 expects text to be scaled up to 200% without loss of content or functionality. This simply can't be done when using the pixel-perfect design technique.

- Performance and Maintainability:

- It encourages the use of hardcoded CSS rather than using scalable design systems and components.

- Modern Design Tools and Systems

- Design Intent Over Exact Replication

- Modern web design focuses on intent and consistency across contexts, prioritising usability and accessibility over pixel-perfect replication by leveraging newly introduced responsive browser technologies.

Can I still use it?

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but no, you can't. It simply isn't compatible with the modern web, for all the reasons I've given above. You are better off understanding what the technique was trying to achieve and focus on modern-day alternatives.

Modern Alternatives

- Use of Design tokens for spacing, colour and typography.

- Modern browser layouts like CSS Grid and Flexbox.

- Component libraries and Design Systems that abstract repeated patterns.

- Focus on the user content, not the dimensions of the UI viewing it.

Pixel-Perfect Summary

Pixel-perfect design was always a terrible design technique that set everyone up to fail with the expectation of pixel accurate designs across browsers and devices. It served its purpose when the web was a lot simpler than it is today. A pixel-perfect design on today's web is a clear indication of an outdated aesthetic, urgently requiring a modern overhaul.

Fixed Pixel Layouts

There's a reason why I've mentioned Fixed Pixel layouts directly after Pixel-Perfect Design. They are related, but have differing concepts. They both emerged in an early era of web design, but they serve different purposes.

Pixel-perfect Design

As you will have just read above, pixel-perfect design emphasises the precise implementation of a design on a website. The output of the website should be identical to the design, down to every pixel. For this reason, it is a philosophy, not a layout strategy.

Fixed Pixel Layouts

Fixed pixel layouts are a layout strategy where all widths, heights, and positions are defined using fixed pixel values (e.g. width: 1024px). This means it the page layout doesn't adapt to different screen sizes or resolutions. They are rigid and non-responsive, and are optimised for a single resolution or screen size. Because of this Fixed Pixel Layouts break on small screen sizes (like mobiles), or large displays. They are very much associated with older websites and legacy intranet tools. If you look at early websites on the web they would often say "Best viewed with Internet Explorer (or Netscape Navigator) at 800×600 (or 1024×768)". These are prime examples of where Fixed Pixel layouts were used.

Fixed Pixel Summary

Fixed pixel layouts and pixel-perfect design are outdated. They are relics from a time when monitor sizes were uniform and browser zooming was uncommon. Pixel-perfect demands you match the design mockup exactly, which usually ends in fragile CSS and breaks the moment someone dares to increase their font size or use a high contrast mode. Fixed pixel layouts take it even further by hard-coding dimensions, making sites fall apart on anything that isn’t a desktop from 2010. Adding to their drawbacks, neither option integrates well with modern accessibility standards, responsive design principles, or current web usage patterns.

CSS Floats for Layout

CSS floats were my go-to layout technique for many years, simply because there really wasn't a viable cross-browser alternative (other than Tables, which I covered earlier in the post). Floats were originally intended to be used for wrapping text around images on a page. They weren't intended to be used for full-page layouts. At the time, designers and developers did this as a creative way to make certain layouts, not because that was the design goal of the CSS specifications.

Common issues

Float-based layouts came with a major issue: fragile designs often required “clearfix” hacks to stop float containers from collapsing.

Example clearfix hacks

Here are a few example hacks that ensured the float container would wrap around the floated elements:

Modern (Recommended):

.clearfix::after {

content: "";

display: table;

clear: both;

}Usage:

<div class="clearfix container">

<div style="float: left;">Left</div>

<div style="float: right;">Right</div>

</div>Overflow Hidden (Quick Fix):

.container {

overflow: hidden;

}This was my personal go to for "clearfix" as it was so simple to add to the CSS. A nasty downside of this method was it would hide any content that needed to overflow outside the float container, so its usage really depended on the design requirements.

Float the Container Itself (Not Recommended):

.container {

float: left;

width: 100%;

}I don't remember really using this method simply because it could interfere with other layout elements on a page and could create unexpected layout shifts during page rendering.

Using display: flow-root (Modern, Clean Alternative):

.container {

display: flow-root;

}This is far too modern for me, it didn't exist when I was still building UI's regularly. As, it has been stable in major browsers since January 2020. The advantage of this method is no pseudo-elements or hacks required. This is recommended for use if you are modernising code and want the cleanest approach without adding extra markup. Other float-based issues include:

- Poor readability: Additional markup was required just for the container clearfix hacks. This also impacted maintainability too.

- Inconsistent behaviour: Floats tended to behave differently depending on the browser in use, although not as problematic as it was, it still requires more testing to ensure cross-browser UI consistency.

- Stacking issues: Aligning text, or centring horizontally and vertically, is non-trivial.

Modern Alternatives

As with most of the topics in this section of the post, there are a list of modern alternatives available for float-based layouts.

- Flexbox: One-dimensional layouts (ideal for nav bars, toolbars, etc).

- CSS Grid: Two-dimensional layouts (ideal for full-page layout and complex structures).

- Media Queries: Enable responsiveness across devices

- Container Queries (still an emerging technology): Context-aware layout changes.

Performance and Maintainability

Modern layout techniques:

- Lead to cleaner and more maintainable code.

- Reduce reliance on utility classes for clearing float-specific bugs.

- Enhance responsiveness and accessibility by ensuring that the HTML code's structure is more predictable.

Legacy Support Considerations

Floats still appear in legacy code, so understanding them remains important for maintenance and modernisation. However, they should be avoided in greenfield projects unless strictly necessary (I'm open to suggestions if anyone has an idea as to what this necessity might be).

CSS Floats Summary

Using CSS floats for layout is now considered an anti-pattern. While historically important, floats have been replaced with modern layout systems like Flexbox and Grid, which offer cleaner, more maintainable, and more powerful solutions. In the future as the web platform evolves, newer layout techniques such as CSS Subgrid, Container Queries, and Anchor Positioning are also progressing through standardisation and will further improve layout flexibility. Avoiding floats is a key best practice when building or modernising frontend architecture.

Faux Columns

I'm not sure why the French word "Faux" was chosen for this technique, rather than just "false" or "fake", maybe to make it sound more appealing? Or more complex than it actually is? The term works though, as in English, it is used to describe something made to look like something else, which is precisely what this technique did.

What is it?

In the early days of CSS there was no reliable way to make two or more columns stretch to the same height when the content length in the columns varied. This was because floats or inline-block elements don't align their heights, so developers looked for a workaround.

How it worked

It was a clever workaround actually, it typically worked like this:

- A background image was applied to the parent container of the floated columns (that designers wanted to look to be equal in height)

- This background image was often a vertical gradient or a solid block of colour. This image was then repeated (

repeat-y) vertically down the parent container, giving the illusion ("fake") that the columns were of equal height. - As each of the inner floated elements extended due to varying content within, the container background image extended with it. Very clever, huh!

The CSS for this "workaround" was as simple as this:

/* container with the background repeat vertically */

.container {

background: url('faux-columns.png') repeat-y;

}

/* Note the width of this column, it is important */

.left-column {

float: left;

width: 200px;

}

/* Use an identical margin to the width, to "push" the right column into place next to the left column */

.right-column {

margin-left: 200px;

}The background image of the container would have 2 sections, one colour for the left column and another for the right column, thus tricking a users eyes into seeing the columns having equal heights!

Check out the Faux Columns A List Apart (ALA) article by Dan Cederholm from January 2004, if you are still unsure how it works, he explained it a lot better than I have!

Limitations

Unfortunately, as with all of these early CSS workarounds, there were limitations. The faux columns technique was no different. These limitations included:

- Not adaptable: it required the background image to perfectly match the layout dimensions of the container, and it's inner "columns".

- Unresponsive: Exactly what the word says, this only worked for fixed layouts, fluid of more dynamic layouts simply broke the illusion.

- Maintenance: The technique was difficult to maintain, since any layout change required editing the CSS, background image, or both.

- Poor semantics: Yes, it solved the visual presentation problem, but the underlying code wasn't semantic, the additional

<div>'s just for layout purposes, inherently held no semantic meaning.

Modern Alternatives

As you would expect, there are modern alternatives that make this layout trivial:

Flexbox

With Flexbox, it really is this simple:

.container {

display: flex;

}

.left-column, .right-column {

flex: 1;

}CSS Grid

In CSS grid, it's even easier as all child elements in a row are explicitly defined and align by default, no extra CSS required:

.container {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(2, 1fr); /* 1fr = 1 fraction unit */

}Can I still use it?

Errr, silly question, no not at all! Look how effortless the modern alternatives above are! Imagine how good it feels to rip out the legacy faux column code from a legacy codebase, and replace it with 1 or 2 lines of CSS!

Faux Columns Summary

The Faux Columns technique was one of those clever hacks we leaned on back when CSS didn’t give designers and developers much to work with. It did the job, but it was fragile and fiddly, and you were always one layout change away from breaking it. These days, it’s more of a historical curiosity. Flexbox and Grid have long since made it obsolete, and with newer tools like Subgrid and Container Queries coming through the standards process, we’ve moved on from trickery to browser tools that are actually built for layout.

Zoom Layouts (using CSS zoom for responsiveness)

Back when responsive design was first emerging, a technique called Zoom Layouts emerged in order to scale whole elements within a UI. This technique emerged because responsive CSS layout techniques were very limited.

Example

An simple example of this is given below:

.container {

zoom: 0.8;

}This CSS is easy to understand, it simply scales the entire .container by 80%.

When was it useful?

This technique was useful when you needed to shrink or enlarge an entire layout without refactoring a fixed-width design. It also came in handy when working with legacy layouts that could not adapt with fluid widths or media queries. Lastly, it was used as a workaround before widespread browser support for the transform: scale() CSS property or relative units like rem, em, %, vw, and vh.

Why is it outdated?

There are a number of reasons as to why the Zoom Layout technique is now outdated. These include:

zoomis non-standard and inconsistent: Thezoomproperty isn't a part of any official CSS specification. It is a proprietary feature initially supported by Internet Explorer, then later Chromium-based browsers. Interestingly, Firefox and Safari have never supported thezoomproperty, making cross-browser layouts using the technique very tricky.- Causes Accessibility issues:

zoomdoes affect the layout scaling, but it doesn't interact well with user-initiated zoom or accessibility scaling preferences. Thus, using this technique can create barriers for users with visual impalements that rely on native browser zooming or OS-level zooming tools. - Breaks layout semantics: zoomed elements don't always reflow correctly, for example text can reflow outside its container, images can become blurry, and form elements may not align correctly when scaled.

- Modern CSS has better solutions: As with most outdated techniques in this post, modern browsers now support much better layout techniques and relative units, that make responsive design much more consistent and easier to maintain. These include Flexbox, CSS Grid and rem, em, %, vw, vh units. Along with Media Queries and container queries, this gives developers the ability to adapt individual elements proportionally, rather than resorting to scaling the entire UI.

- Performance issues: The use of

zoomcan cause serious performance issues, especially on low-powered devices since the rescaling causes the browser to scale rasterised layers rather than reflow content natively, which increases UI repaint costs.

Can I still use it?

Seriously, only if you hate your users and love additional maintenance. In practical terms, using it would not be a responsible choice; avoid it. If you come across a critical legacy site using this approach, plan to refactor it with modern techniques. Build your layouts using CSS Grid or Flexbox for flexibility across breakpoints, implement fluid typography with clamp and viewport units, adopt container queries for component-level responsiveness, rely on viewport-based units for consistency, and always test with browser zoom and assistive technologies to ensure accessibility and adaptability for all users.

Zoom Layouts Summary

Using zoom for layout responsiveness is an outdated, non-standard technique that can compromise accessibility, compatibility, and performance. Modern responsive design principles provide far more robust, scalable, and accessible solutions.

If you require a transition approach for legacy systems still using Zoom Layouts, consider refactoring incrementally to CSS Grid and Flexbox combined with relative units like rem or percentages to modernise their responsiveness. Luckily for you, this isn’t the last time you’ll hear about the infamous proprietary zoom property, as it makes quite a few appearances later in the blog post when we dive into those classic IE layout quirks.

Nested ems instead of Pixels

Before the CSS rem unit was added to the CSS Values and Units Module Level 3, developers used the em unit as a responsive strategy to avoid fixed pixel font sizes. Having used it for years I can confirm it was a real pain in the ass to work with (pardon my French!). When using an em unit, both the CSS font size and spacing were sized relative to their immediate parent container.

For example, given this HTML:

<body>

<div class="container">

<p class="child">Some text here</p>

</div>

</body>And this CSS:

body { font-size: 1em; }

.container { font-size: 1.2em; } /* relative to body */

.child { font-size: 1.2em; } /* relative to .container, so compounded */Can you guess what the .child font size of the text is in pixels?

Better get your Math(s) hat on, let's go through it!

Default body font size = 16px so 1em x 16px = 16px. The

.containerDIV is relative to the body font size so:.containerfont size = 1.2em x 16px = 19.2px. The.childparagraph is relative to the.containerfont size so:.childfont size = 1.2em x 19.2px = 23.04px

That's right, that well-known font size 23.04px!

Now this is just a very basic example, imagine if you include em units for margins and paddings too! And also layer on additional nesting! Hopefully, you are starting to realise how painful em units were to use on a website, especially when the only viable alternatives were percentages (which had the same relative nesting issue and were even less intuitive to use than em), or CSS keywords e.g. font-size: small, medium, large, x-large, etc. As you can see, there weren’t a lot of viable or maintainable options in terms of responsive typography and spacing in the early responsive design era (around 2010-2013).

Why it's outdated?

- Complexity and unpredictability: Nested ems lead to compounded calculations as we saw in the simple example I gave above, making sizing unpredictable in deeply nested components. A small change in a parent font size cascades unexpectedly and could completely obliterate your well-crafted layout.

- Maintenance overhead: Adjusting layouts or typography with nested ems quickly creates brittle CSS and significant technical debt, especially when ems are used for spacing like margins and padding.

- Inconsistent UI scales: Components may render differently in different contexts if they rely on em units, especially in large applications with diverse layout containers.

Modern Alternatives

You can utilise several modern options for nested em units. These include:

- rem units for consistent global scaling relative to the root font size

- Clamp-based fluid typography for responsive design, for example Utopia.fyi.

- CSS custom properties (variables) for consistent, maintainable scales

Can I use them today?

You could, but I have no idea why you would! When more viable alternatives exist today like rem units for global scaling, clamp for fluid typography, and CSS variables for maintainable scales, why make life harder than it needs to be??

Nested ems Summary

Using nested em units is outdated. It adds unnecessary complexity and unpredictability. For modern responsive design you are far better off using rems for consistent global scaling, or taking advantage of the clamp CSS function if you are feeling adventurous. Lastly, you could always use modern CSS variables for more consistent and maintainable code.

Setting the browsers base font size to 62.5%

As a direct follow on from the nested em technique earlier in the post, there was an alternative that developers came up with to simplify the math(s) behind percentages (since they had the same "relative to parent" issue as em's). When developers decided to use percentages for fonts, they often set the font size on the <html> element to:

html { font-size: 62.5%; } /* default font size now 10px not 16px, due to scaling making `em` units easier to work with (base-10 rather than base-16) */

.container { font-size: 1.6em }/*16px*/

.container { font-size: 2.4em }/*24px*/

.container { font-size: 3.6em }/*36px*/This avoided complicated fractional calculations when using em units:

- Without the percentage: 1em = 16px → 24px = 1.5em.

- With the percentage: 1em = 10px → 24px = 2.4em.

You still had the problem with nested elements, but that was later fixed by using rem units (root em).

Why are these techniques less common today?

- It overrides user defaults: Some users may increase their base font size from 16px for accessibility reasons, hard-coding the base size to 62.5% undermines this user preference.

- Modern teams work with

rem: Most developers and teams now accept that 1rem = 16px and use design tokens, variables, or a spacing scale instead of forcing a base-10 (62.5% hack) mental model. - Simplicity from Modern tooling: Design systems, utility classes, and CSS variables handle sizing scales more predictably without the 62.5% hack.

Can I still use it today?

No, not really, mainly due to the list of reasons I've given above. font-size: 62.5% was merely a developer convenience hack to make 1em / 1rem equal 10px for easy math(s). Look at the short list of modern alternatives I have listed above instead.

Base font size Summary

As mentioned above, this math(s) hack for easier font sizing is no longer required on the modern web, in fact it should be avoided due to the impact it has on users who change their base font size for accessibility reasons. Look to use one of the more modern techniques mentioned in the "Why are these techniques less common today?" section above.

Fixed-Width Fonts for Responsive Text

Fixed-width fonts are better known as monospaced fonts, they allocate the same horizontal spacing to each character. For example:

.mono-spaced-font {font-family: Courier New,Courier,Lucida Sans Typewriter,Lucida Typewriter,monospace;}The example provided above demonstrates how to render text in a monospaced font and concurrently defines a monospaced font stack for most web page implementations. The reason I say "most" is because Windows has a 99.73% support for Courier New and OSX has 95.68% support according to CSSFontStack. Which is why it is listed first in the font stack, for the less than 1% of users that don’t support it, the browser will look for Courier and so on, until it gets to the end of the font stack, where it just tells the browser to use any monospace font the system has available.

Historically, monospaced fonts were used for:

- Terminal emulation.

- Code editors for alignment.

- Early web design, where the layout predictability was prioritised over aesthetics or responsiveness.

Why was the technique used in responsive text?

Developers and designers struggled with the web platform's limitations at the time due to a lack of suitable tools. So monospaced text was usually used for:

- Consistent character spacing across browsers.

- Easier text alignment in table-based layouts.

- Simplifying calculations for layout sizing, since browser layout strategies were much less mature than they are today.

Why is the technique outdated?

The technique is now considered outdated for various reasons, including:

- It limits design flexibility. Modern responsive design has moved on from fixed typography, as fluid typography is now possible, which is better served by proportional fonts that adapt visually to varying screen sizes and reading contexts.

- Monospaced fonts are harder to read, especially for paragraphs or long text blocks. This requirement on the modern web is critical for accessibility-focused design.

- Instead of outdated methods, modern CSS offers enhanced tools and support for contemporary layout techniques. Flexbox and CSS Grid, coupled with various typography scaling units like

rem,em,vw,vh, andclamp(), enable more predictable and reliable layout control. - There's no performance difference between modern proportional fonts and monospaced fonts, they both have similar browser overhead, so why choose a technique that is harder to maintain and comes with a whole host of other disadvantages?

What's a modern replacement?

There are a number of modern alternatives, some of which we touched on above. These include the use of:

- Fluid typography with CSS

clamp()and viewport units to ensure text scales responsively across devices. - Proportional fonts with font fallback stacks to optimise readability and layout adaptability.

- Only using monospaced fonts for semantic or functional reasons, not aesthetics. Code blocks and tabular data are prime examples of where monospaced fonts should be used to enhance readability of these certain areas of a website. Adventurous designers can even transform a web UI into a retro Terminal window with these elements, though readability must be carefully considered.

Can I still use it?

As stated repeatedly in this section of the blog post, while technically possible, it would be highly illogical to employ this technique. Given the numerous disadvantages outlined earlier in this section, utilising such an antiquated method on the modern web would be ill-advised.

Fixed-Width Fonts Summary

There are so many font options available to developers and designers today. There is no way you should ever use a monospaced font for anything besides sections of code, or possibly text in a data table, depending on what type of data you are wishing to display. In both of these cases, a monospaced font can enhance readability if used correctly.

4. The Plugin Era – Flash and Friends

Flash-Based Content

I distinctly remember having a conversation with a then colleague regarding iOS not supporting Flash content and how it was the beginning of the end of Adobe Flash (Flash) on the web. At the time he refused to believe it, but thankfully for the web, my prediction came true!

What was Flash-based content?

Flash was a proprietary multimedia software platform developed by Adobe. It was used to:

- Deliver animations, video, and interactive content via a plugin in the web browser.

- Enable rich media applications embedded in websites.

- Power early interactive interfaces on the web, this was way before the web platform matured and could support these types of interactivity natively.

- I, personally, remember it for flash-based advertisements of which I created many when I was first starting out in web development!

Why was it popular?

Flash was hugely popular at the time due to the fact that:

- Cross-browser multimedia support was lacking on the web platform (i.e. no native support)

- Advanced vector animation support

- In 2005, Flash was the sole method for streaming audio and video on the web, as exemplified by YouTube's reliance on it.

- Interaction was programmed through the use of ActionScript. If it sounds very familiar to JS, that's because it is, as they are both based on the ECMAScript Standard. That's a massive oversimplification, but if you are curious, read all about it on Wikipedia.

- In the late 1990s there was a popular trend on the web of having completely pointless Flash intros that would load and play automatically before you entered a site. There are countless example of these intros on YouTube if you are interested!

Why was it deprecated?

There are many reasons as to why Flash is now deprecated. These include:

- Flash was well-known for serious security vulnerabilities, which were often used for malicious software and browser takeovers.

- Flash content often consumed significant CPU and memory, leading to poor performance and excessive battery drain on mobile devices.

- As mentioned earlier, Apple refused to support Flash on iOS, citing security, performance, and stability concerns, which contributed heavily to its decline.

- Adobe's proprietary Flash technology was incompatible with open web standards, hindering accessibility, interoperability, and sustainability.

- Lastly, open web standards and the web platform evolved to replace Flash with native (and non-proprietary) functionality like:

- Native video and audio playback (

<video>and<audio>tags) - CSS animations and transitions

- Canvas and WebGL for interactive graphics and games

- SVG for scalable vector graphics

- Native video and audio playback (

Flash met its end with the advent of modern web APIs, including HTML5, CSS3, and modern JS.

In 2017 Adobe announced that Flash's end of life would be in 2020. In December 2020 Adobe released the final update for Flash. By January 2021, major browsers disabled Flash by default and eventually blocked Flash content entirely.

Can I still use it?

At last! A straightforward answer to this question: No, it's impossible for you to use Flash on the modern web as Flash content in no longer supported in any modern browser. Simple! RIP Adobe (Macromedia) Flash 1996 to 2020. You won't be missed.

Modern Alternatives

As mentioned above, there are a number of native browser-based alternatives for Flash (HTML5, CSS3, Modern JS) functionality these are: - Native video and audio playback (<video> and <audio> tags) - CSS animations and transitions - Canvas and WebGL for interactive graphics and games - SVG for scalable vector graphics

Scalable Inman Flash Replacement (sIFR)

Before the introduction of the @font-face at-rule, which is defined in the CSS Fonts Module Level 4 specifications, Web Designers and Frontend Developers were desperately seeking to expand the limited number of cross-browser, and cross-operating system fonts that were available on the web. In order to achieve that, a number of workarounds and general ingenious browser hackery were built. From the name of this technique you may also be able to guess the answer for the "Can I still use it?" section!

What is sIFR?

Scalable Inman Flash Replacement (sIFR) was an creative technique that used JS and Flash together to replace HTML text elements with Flash-rendered text. This feature allowed developers to embed custom fonts directly within the Flash file. Consequently, they could modify the HTML text, and the Flash file would dynamically render the updated content.

This workaround was required at the time because there was very limited support for custom web fonts via the use of @font-face. Surprisingly, @font-face was first introduced by Microsoft in Internet Explorer 4 in 1997, using Embedded OpenType (EOT) as the font format. This was proprietary to IE, so no other browsers supported it. Since there wasn't a cross-browser way to use custom fonts, alternative techniques like sIFR emerged.

sIFR Popularity

sIFR emerged in the early to mid-2000s, with its first public version released around 2004-2005. sIFR was widely used until around 2009-2010, especially for headings and branded typography. Its popularity grew during that period due to the technique's preservation of SEO and accessibility advantages. This was because the original HTML text remained in the Document Object Model (DOM), allowing it to still be readable by search engines and assistive technology. And once setup it was simple to update the underlying text and sIFR took care of the rest. There was also the added bonus that the text remained selectable, so could be copied and pasted when needed. It sounds like a great solution, so where did it all go wrong?

Why it's outdated?

There are several reasons why the sIFR technique is now outdated. We covered the main one in the previous "Flash-Based Content" technique above:

- It relies on the Adobe Flash Player browser plugin, that is now deprecated and blocked in all major browsers due to security vulnerabilities and performance issues.

- It slowed down page performance by increasing page load time, due to having to download the Flash assets.

- Although it was partially accessible from an HTML perspective, it certainly wasn't perfect as it introduced accessibility and compatibility issues on devices without Flash support.

- Web standards came to the rescue. CSS3 brought with it native cross-browser support for

@font-facefor custom fonts, without the need for any browser plugins. The new standards supported Web Open Font Format (WOFF and WOFF2) font formats which are a standardised and optimised custom font format for the delivery of fonts on the web. Basically, HTML5 and CSS working together simply removed the need for plugin-based typography workarounds.

Can I still use it?

As I mentioned, above this is a pretty simple question to answer… No, not at all, the removal of Flash from all modern browsers used today guarantees that!

Modern Alternative

There's only one modern alternative that should be used on the web today: @font-face. An example of its usage is given below:

@font-face {

font-family: "MyCustomFont";

src: url("fonts/MyCustomFont.eot"); /* IE9 Compat Modes */

src: url("fonts/MyCustomFont.eot?#iefix") format("embedded-opentype"), /* IE6-IE8 */

url("fonts/MyCustomFont.woff2") format("woff2"), /* Super modern browsers */

url("fonts/MyCustomFont.woff") format("woff"), /* Modern browsers */

url("fonts/MyCustomFont.ttf") format("truetype"); /* Safari, Android, iOS */

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}Thankfully, modern browsers widely support WOFF, thus, simplifying the above code:

@font-face {

font-family: "MyCustomFont";

url("fonts/MyCustomFont.woff2") format("woff2"), /* Super modern browsers */

url("fonts/MyCustomFont.woff") format("woff"); /* modern browsers */

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}In fact, any modern web browser that supports WOFF also supports WOFF2. Therefore, the code you should use today is as follows:

@font-face {

font-family: "MyCustomFont";

url("fonts/MyCustomFont.woff2") format("woff2");

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

}In all instances above you'd use the custom font like so:

.myfontclass {

font-family: "MyCustomFont", /* other "fallback" fonts here */;

}The browser will take care of the rest!

Note: that you should always provide a font fallback in your font-family property, just in case the font file fails to load, or it is accidentally deleted from your server. There is so much more to the use of @font-face. If you are interested in advanced topics around its usage you should definitely check out Zach Leatherman's copious amount of work on the subject over the years!

Cufón

Much like sIFR above, Cufón was created due to the lack of options when it came to using custom fonts on the web. It was popular around the same time as sIFR (late 2000s and early 2010s). It essentially was solving the same problem, but using a different cross-browser technique. Whereas sIFR used Flash, Cufón worked like so:

- Fonts were converted into vector graphics, and canvas (or VML for older versions of IE) this was then used to render the text in place.

- The JS then replaced the HTML text with the custom font rendered version of the text.

- Since it was JS-based, there was no need for any plugins (like Flash).

Why was it used?

As previously noted with sIFR, browser support for CSS @font-face was inadequate or inconsistent at the time. Designers and developers wanted to use custom fonts for branding and stylistic reasons without users having to install a plugin or the fonts locally. Cufón was attractive because it:

- Didn't require a plugin for it to work.

- Provided near pixel-perfect rendering of the custom font.

- Was easy to integrate with minimal JS setup.

Why is it outdated?

- Modern browsers all support

@font-face, a much better solution as it allows the direct use of web fonts like WOFF or WOFF2 files without the use of JS hacks. - Its usage impacted accessibility. Due to Cufón replacing text in the DOM with rendered graphics, screen readers couldn't interpret these replacements as text, thus degrading a site's accessibility.

- Cufón caused web performance issues as the text replacement script was run after page load, which increased page render time, blocked interactivity and degraded the overall performance, especially on slower devices.

- Although Cufón attempted to preserve the replaced text in the DOM, the results were often inconsistent, mainly because search engine crawlers at the time had inconsistent results when parsing JS-replaced content.

- Cufón didn't work with responsive design, once rendered the Cufón replaced text didn't scale correctly, unless the page was reloaded at the new page size.

Can I still use it?

Although the site is still available here, and the cufon.js script is still available to download. The font generator has been taken down and is no longer maintained. So to get it working you'd need to jump through quite a few hoops! So, what I'm really trying to say is: Yes, you can, but it isn't worthwhile. Even the original author Simo Kinnunen says on the website:

Seriously, though you should be using standard web fonts by now.

Modern Alternatives

Rather than repeat myself, I'll refer you to the same section from the sIFR methodology above.

GIF Text Replacements

Although I am aware that this is not a plug-in, it seemed like the most appropriate section to include it in since we are discussing font replacement techniques. Of all the custom font techniques I've listed, this one is by far the worst in my opinion. The technique was popular in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, when there were very few other options for using custom fonts on the web.

What is a GIF Text Replacement?

It's a self-explanatory name. In order to use a custom font, a designer would create the static asset (usually via Photoshop or similar), then the developer would cut out the text as a GIF. This image would then be used to replace the HTML text on the page with the image, in order to make it look like a custom font was in use. Example code for this technique can be seen below:

<body>

<!-- Gif text replacement for a heading -->

<h1>

<img src="images/heading-text.gif" alt="Welcome to Our Website">

</h1>

<ul>

<li>

<!-- Gif text replacement for a navigation link -->

<a href="/about.html">

<img src="images/about-link.gif" alt="About Us">

</a>

</li>

</ul>

</body>Note: Some readers may wonder why a GIF was used instead of a PNG, since both support transparency. The main reason is that Internet Explorer offered poor support for transparent PNGs and required a complicated hack to make them work, which I will explain later in the post.

Why was it so bad?

- It was time-consuming and maintenance heavy. Should the design change, then so would all the GIFs that had to be manually cut out of the design files again.

- It was bad for Accessibility. Screen readers are unable to process text embedded within GIFs or images that lack meaningful alt text. The absence or outdated nature of alt text therefore created an exclusionary experience for users with visual impairments.

- It was bad for SEO. Search engines could not index text within images, thus, harming discoverability, this technique relied on developers ensuring they had accurate alt-text, which isn't always the case.

- It was bad for performance. At the time of its popularity, the web was going through a transition period from HTTP/1.0 to HTTP/1.1. Although HTTP/1.1 was better for TCP connections than HTTP/1.0, these TCP connections were very expensive in terms of web performance, and each of these GIF replacements required its own TCP connection, which increased page load times.

- It was terrible for responsiveness. Although the responsive web was a few years away when it was popular, the difference between images and text rendering was text's ability to scale across different devices and screen sizes. Images simply couldn't do that, leading to poor rendering and pixelation on some devices.

- GIF only supports 256 colours (8-bit) and for the GIF to be transparent, one of those colours would need to be transparent. So if your text had a complex colour palette, it either wouldn't work, or just look terrible.

Can I still use it?

No, it's as simple as that. It's a technique with so many negatives and so few positives, it should be confined to the interesting history of the web platform!

Modern Alternatives

Again, rather than repeat myself, I'll refer you to the same section from the sIFR methodology above.

Adobe AIR

I remember going to a conference around 2007 / 2008, and there was so much hype about Adobe AIR. It was going to be the "next big thing", due to the fact it could enable developers to create rich desktop and mobile apps using only web skills and technologies.

What was Adobe AIR?

The AIR in Adobe AIR stood for Adobe Integrated Runtime. It was a cross-platform runtime developed by Adobe. It allowed developers to use: HTML, JS, Adobe Flash, Flex, and ActionScript. All combined they could run as a standalone desktop or mobile application. It supported Windows and macOS for desktop, and later Android and iOS on mobile.

Furthermore, it also enabled:

- Running Flash-based applications outside the browser.

- Enabling rich multimedia, animations, and offline capabilities.

Why is it outdated?

- It relied on Flash and ActionScript. With flash reaching its end of life in late 2020 due to persistent security vulnerabilities, and the momentum behind open standards like HTML5, CSS3, and JS ES6+. AIR ceased to exist due to the loss of its core technology.

- A shift to modern cross-platform frameworks. The market moved towards more efficient and performant technologies like:

- React Native

- Flutter

- Electron (for desktop apps) The advantage of these frameworks is they use native components or JS runtimes, without the heavy reliance on Flash. This offered developers and users greater performance, maintainability, security, and community support.

- Lack of Adobe support. Adobe handed AIR over to a subsidiary of Samsung (Harman) in June 2019for ongoing maintenance. Support is still provided by Harman, but only for enterprises with legacy applications that they still rely on, There's no active innovation or features being added to AIR by Harman.

- Security concerns. As with Flash in the browser, security was always an ongoing issue, and this continued in AIR since it was the backbone to its core functionality. By continuing to build on AIR, it poses security risks and compatibility limitations with modern browsers and operating systems.

- Lack of developer interest and ecosystem. Developers on the modern web tend to favour open ecosystems with an active community for support and updates. Adobe AIR’s ecosystem has completely stagnated.

Can I still use it?

As with any other Flash-based technology, I'm afraid not, it is no longer supported and even if you could, there are more modern open frameworks you could use like, React Native, Flutter, or Electron (for desktop applications). AIR is now history, and if you are using an AIR application within your digital estate, it is strongly recommended you prioritise migration, due to higher maintainability, poor security, and lack of developer availability.

Yahoo Pipes

It is easy to forget just how dominant Yahoo was on the web during the late 1990s. Before Google emerged as the leading search engine, Yahoo was one of the primary gateways to the internet. Its peak influence was between 1996 and 2000, when it played a central role in how people accessed and navigated the web. It was the default starting point for most web users due to its curated directory, news, and email services combined. It was also a technology leader on the web too, as I mention later in the blog post when I look at their extensive JS Library: Yahoo! User Interface (YUI).

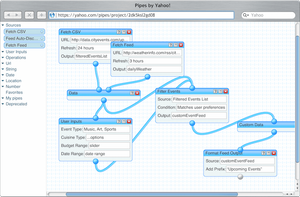

I remember using Yahoo Pipes for combining my many RSS feeds at the time, it really was a fantastic visual tool for data manipulation.

What was it?

Yahoo pipes was a visual data mashup tool that allowed users to aggregate, manipulate, and filter data from around the web. It was released in 2007, and it allowed developers (and non-developers) alike to aggregate, manipulate, and filter data from around the web. It provided a drag and drop interface where users could connect various manipulation modules and join them together by creating pipes between modules. You were essentially piping data "through" the tool (hence the name!) and the manipulated date would come out the other end. It was considered highly innovative at the time, and it was used a lot for rapid prototyping.

Why is it outdated?

Have a look at the Yahoo! homepage, and you will see it is the shadow of its former self, it looks to more of a news aggregation service now than a popular search engine. This was because Yahoo decided to make a giant shift in business strategy, moving away from developer tools and open web utilities to concentrate on advertising and media products. Although it was popular with technology enthusiasts, it was never a mainstream product for Yahoo, so the operational expenses vs. usage statistics didn't align with Yahoo's business priorities. Lastly, the web evolved beyond Yahoo Pipes, and it couldn't keep pace with the changes. Modern APIs, JSON-based services, and JS frameworks allowed developers to build similar data transformations programmatically with greater flexibility. Due to all these factors Yahoo Pipes was sadly shut down in 2015.

Can I still use it today?

Nope, it was shutdown by Yahoo in 2015, with no further support or hosting by Yahoo.

Modern Alternatives

While innovative at the time, visual mashups have been replaced by:

- Dedicated data transformation tools (e.g. Zapier, Integromat/Make).

- Serverless functions (AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, Cloudflare Workers, and Fastly Compute@Edge) for real-time data processing.

- Low-code platforms with integrated API management.

The web has also become a lot more complicated regarding Web scraping and feed aggregation. Because anti-scraping measures, authentication, and API rate limits weren't necessary when Yahoo Pipes was created, the techniques it employed didn't support the robust backend processes now required to handle these requirements. Although Yahoo Pipes was innovative at the time, it has long been discontinued and is now considered a obsolete part of web platform history.

PhoneGap / Apache Cordova

The one thing that sticks in my mind when I think about PhoneGap is when I saw a talk from one of the Nitobi engineers back in 2009 / 2010, he said something along the lines of: